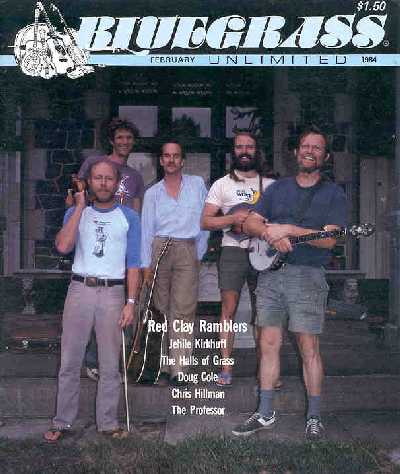

On the cover of Bluegrass Unlimited

The Red Clay Ramblers: New Time Music

[Webgal's note: This article contains a lot of the Red Clay Ramblers' history as well as biographical information on each Rambler.]

By Al Steiner

The Red Clay Ramblers are not a bluegrass band, and they do not play “Rocky Top.” You may see them on occasion picking away on an old-time square dance number with a lineup of fiddle, mandolin, banjo, bass and piano, but they’re not exactly an old-time band either. Pinning any label on this band is difficult. Some call their work “new-time music.” One reviewer dubbed the Ramblers “America’s premier ‘whatzit’ band.”

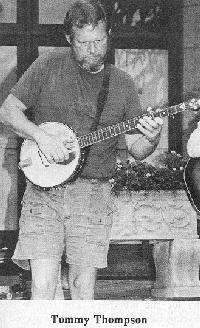

The Ramblers’ forays from their base in old-time music into the blues, Irish music, early jazz, contemporary folk, college glee club tunes, western swing, gospel and yes, bluegrass, contrast with the pure revivalist approach of the group with which Tommy Thompson, one of the founding members of the Ramblers, first recorded. That band, the Hollow Rock String Band, concentrated solely on old-time dance music learned directly from older fiddlers and banjoists. There were no vocals, no instrumental solos and no original tunes, as there are with the Red Clay Ramblers. There was no use of the trumpet and piano, and outwardly, there was not much humor.

A typical Ramblers’ performance covers that wide spectrum of music, and each of the five members contributes vocally and instrumentally in a variety of ways. In a single set, the band may do a college glee club tune like “Talk About a Jerusalem Morning,” then break down into a trio for a couple of Carter Family tunes, come back with a rollicking old-timey number by the full band, do an original song, play a contemporary number like Si Kahn’s “Aragon Mill,” hit a bluegrass-style gospel tune like “I Don’t Want to Sing in Satan’s Choir,” do an old-time novelty number like “C-H-I-C-K-E-N” and then break down into a duo for some Irish tunes on fiddle and mandolin.

The Ramblers don’t like to be thought of as a novelty-song band, but they have done their share of humorous numbers during a career spanning ten years and six albums. They play Egyptian style old-time music on “I Crept Into the Pharaoh’s Crypt and Cried,” one they picked up from Homer and Jethro. Thompson has contributed some original rib-ticklers, including what may be the band’s best-known tune, “Merchants Lunch.” The band’s sense of humor carries through to their stage act. At a recent performance, Rambler Jim Watson commented on the loudness of Thompson’s attire by politely asking the soundman, “Can we have a little less shirt in the monitors?”

The Ramblers got their start

in Chapel Hill, North Carolina in 1972. Tommy Thompson, who plays

banjo and guitar, formed the band along with fiddler Bill Hicks and Jim

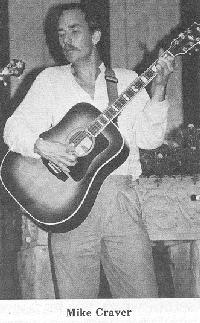

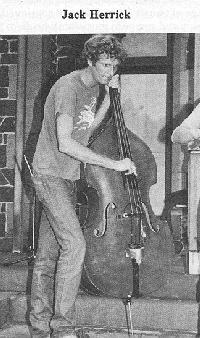

Watson, who plays mandolin, bass and guitar. Late in 1973, Mike Craver, a pianist, guitarist and bassist, became a Rambler. Jack Herrick

officially joined the band in early 1976 as a bass player, and he now handles

trumpet, pennywhistle, harmonica and a little bit of Irish-style mandolin,

too. In 1981, Bill Hicks chose to give up touring, and Clay Buckner

took over his post.

a pianist, guitarist and bassist, became a Rambler. Jack Herrick

officially joined the band in early 1976 as a bass player, and he now handles

trumpet, pennywhistle, harmonica and a little bit of Irish-style mandolin,

too. In 1981, Bill Hicks chose to give up touring, and Clay Buckner

took over his post.

The Ramblers like to explore different vocal and musical texture. Tommy and Jim both have the ability to switch from growling and shouting vocals to a more sensitive approach, as the situation demands. Mike can do his best to sound like Sara Carter or sing sentimental pop numbers. Jack and Clay do leads mainly on novelty songs. According to Mike, “Everybody kind of has a hand in” arranging the vocal harmonies. “It’s funny. We’ll start singing ‘em one way and a year later, they’ll have changed so drastically from how they were originally formulated that nobody can say where they come from.” Musically, there are few bands that have arrangements as clever as the Ramblers’. What other band has unison parts for clawhammer-style banjo, trumpet and piano? The intricate arrangements are group efforts, but whoever brings the song in usually makes an initial proposal.

The piano, although used occasionally in old-time music through the years, was not exactly a fixture in the string band lineup. When Mike joined the band, he played a lot of bass at first. “We weren’t sure how the sound was going to go,” Mike recalled. “It was a real traditional band, and we didn’t want to do anything too untraditional.” So, the band worked in the piano a little bit at a time and made tentative musical explorations.

The trumpet has had little

use in the old-time string band tradition, although it did find a home

in Jimmie Rodgers’ music and in western swing bands. When Jack joined

the Ramblers, he also played a lot of bass at first. The trumpet

“seemed a little out of place,” said Jack. “Then we started doing

more New Orleans tunes and Charlie Poole tunes—we started adding trumpet

in on a few of those—and we started doing a few blues.”

The Ramblers take solos,

and those are rarely heard in traditional old-time music. The decision

to take solos “wasn’t so much a decision not to be old-timey, as it was

a decision to be more true to ourselves, just to do what we felt like doing,”

Mike explained. “Jack and I came out more of a college band tradition.

I played in a rock band, and people always took solos in them.”

Jim Watson “wasn’t really concerned about whether we were strictly an old-time band or not. I was willing to try anything if it sounded to me like we were doing it O.K., that was fine with me…So far, we haven’t stumbled yet.”

Tommy Thompson admitted that as more old-time revivalist bands started and re-recorded the tunes learned from old 78s that there simply was less material to go around that was both fresh and decent. That was one reason the Ramblers began to expand their horizons, but, said Tommy, “there’s more to it than that.”

“You play that kind of music for a while, and you get to the point where it’s not that you couldn’t get any better at it, but you don’t feel like you’re really doing anything anymore… It begins to feel like you’re simply not creating anything. And if you’re not creating anything, then you might as well think of your music as a hobby…like model railroading. If you’re not making a difference in the world, then you have no business out there putting on a show. If you’re going to earn your living that way, you’re going to get up on stage and make a statement, then you have to have something to say.

“And the only way you can do that is to try new things. We felt like, for one thing, that…we had a much vaster body of friends who weren’t old-time music buffs than who are, and we wanted to be able to play to people who had good taste, but maybe weren’t already aficionados of old-time music.

“It stimulates you to write songs. When you write a song, you may be influenced by the old-time songs that you’ve known…yet at the same time, it’s really you trying to say something…to speak for yourself, your own generation, to your own generation. It’s a likeable feeling, to feel like you’re not isolated by an interest in what the rest of the world views as obscure and antiquarian, that you’re really a part of your own times. But that’s a nice feeling of wholeness to bring the past and present together. So we write a song and then give it an acoustical instrument treatment that’s partly traditional and partly new. That just feels like you’re doing more.”

Thompson’s contributions

to the Ramblers’ repertoire include “Twisted Laurel,” his song about  West

Virginia, the somewhat mysterious number “Regions of Rain” and “The Miracle

of Watermelon Park,” which describes a rather uplifting experience at a

bluegrass festival in which the stage musicians and all, floats heavenward

from the festival ground. “Merchants Lunch,” a gem that Tommy co-authored

with Mike Craver tells a nightmarish but humorous tale. A Texas-based

trucker stops for the Blue Plate Special at the Merchants Lunch in Nashville.

There he is confronted by a rat-faced manager and an imposing waitress

named Broadway Brenda with teeth “as green as garden peas” who holds forth

with her “Derelict Court.” The trucker makes a quick exit, getting

“back to Beaumont for the evening news,” and swears he’ll keep his rig

in Texas, saying “I ain’t leavin’ for snacks.”

West

Virginia, the somewhat mysterious number “Regions of Rain” and “The Miracle

of Watermelon Park,” which describes a rather uplifting experience at a

bluegrass festival in which the stage musicians and all, floats heavenward

from the festival ground. “Merchants Lunch,” a gem that Tommy co-authored

with Mike Craver tells a nightmarish but humorous tale. A Texas-based

trucker stops for the Blue Plate Special at the Merchants Lunch in Nashville.

There he is confronted by a rat-faced manager and an imposing waitress

named Broadway Brenda with teeth “as green as garden peas” who holds forth

with her “Derelict Court.” The trucker makes a quick exit, getting

“back to Beaumont for the evening news,” and swears he’ll keep his rig

in Texas, saying “I ain’t leavin’ for snacks.”

“There is a Merchants Lunch in Nashville,” Tommy explained, but there is only a little truth to the tale, “At the time we were there, it wasn’t a particularly savory place to be. There was a rat-faced manager. Everybody there looked bruised. There were a lot of people there with casts on and things.” However, “there is no Broadway Brenda,” and there was no Blue Plate Special.

Tommy was born in 1937 in West Virginia near Charleston in a fairly urban part of the state. He spent his teenage years in north Florida and attended college in Ohio. After joining the Coast Guard and spending four years in New Orleans, Tommy moved to Chapel Hill in 1963 to work toward a doctorate in philosophy at the University of North Carolina. He already had an interest in folk and traditional music and was playing some banjo, and that was one reason he chose North Carolina as the locale for his graduate study.

Tommy started to go to fiddler’s conventions and met others from the Chapel Hill-Durham area who were interested in old-time dance music. Around 1965, he helped form the Hollow Rock String Band. The other band members were fiddler Alan Jabbour, a grad student in English at Duke, mandolinist Bertram Levy, a Duke med student, and guitarist Bobbie Thompson, Tommy’s wife, who was a book designer at the Duke University Press. Jabbour had done a lot of fieldwork, collecting fiddle tunes, and he was the source for the group’s material. The band was named for the little town outside of Chapel Hill where the Thompsons lived. “The only reason we needed a name was because we liked to go to the fiddler’s conventions and get in the contests,” and they required bands to have names, Tommy remarked.

The band was a sideline, just a hobby for the members. The Hollow Rock String Band never toured and played for money only a few times, but the band’s existence and career was significant for the old-time music revival in the South. “We thought we were doing something that had never really been done before, and we were right,” Tommy said. “We had gotten together for the sole purpose of playing those dance tunes learned directly from old-time fiddle players…And had a bunch of material that almost none of …had ever been recorded before. We were the only band that we knew of that concentrated on that particular form of music.”

The Kanawha label released an album of the band’s music in 1968 (Traditional Dance Tunes, Kanawha 311). Many of the tunes came from old-time fiddler Henry Reed of Glen Lyn, Virginia. Soon after the release of the record, the band members went their separate ways, although all continued to play old-time music. Alan Jabbour ended up in Washington, D.C. with the Library of Congress. Bertram Levy recently put out an album of tunes played on a nylon-strung banjo (That Old Gut Feeling, Flying Fish FF 27271). Bobbie Thompson played with another Chapel Hill-Durham area group, the Fuzzy Mountain String Band, and appeared on the band’s first Rounder album. She passed away prior to the recording of the band’s second LP. The Fuzzy Mountain String Band dedicated the album to her, and her artwork adorns the cover. Rounder later came out with a second Hollow Rock String Band album, with Alan, Tommy and Jim Watson, recorded in 1972, but the band existed only as a “state of mind” at that point. More recently, Alan and Tommy linked up with guitarist Sandy Bradley on a recording called Sandy’s Fancy (Flying Fish 260). The album included more tunes learned from Henry Reed. (See our Hollow Rock String Band section for ordering info on any of these recordings.)

Jim Watson, 35, from Durham,

began to play mandolin in 1968, around the time he met Tommy  and

some of the other members of the Hollow Rock String Band. Jim started

learning fiddle tunes, going to jam sessions and, he said, “making a nuisance

of myself.” Tommy and Jim teamed up in 1969 and then added fiddler

Al McCanless and performed as a trio for much of 1970. After Jim

graduated from college, he moved away from the Chapel Hill area for about

a year and a half. Tommy, who completed all but the dissertation

in his graduate work in philosophy, also left the area, moving to Birmingham,

Alabama for a teaching job. When Tommy returned to the area in 1972,

he and Jim joined forces with fiddler Bill Hicks of the Fuzzy Mountain

String Band and started the Red Clay Ramblers.

and

some of the other members of the Hollow Rock String Band. Jim started

learning fiddle tunes, going to jam sessions and, he said, “making a nuisance

of myself.” Tommy and Jim teamed up in 1969 and then added fiddler

Al McCanless and performed as a trio for much of 1970. After Jim

graduated from college, he moved away from the Chapel Hill area for about

a year and a half. Tommy, who completed all but the dissertation

in his graduate work in philosophy, also left the area, moving to Birmingham,

Alabama for a teaching job. When Tommy returned to the area in 1972,

he and Jim joined forces with fiddler Bill Hicks of the Fuzzy Mountain

String Band and started the Red Clay Ramblers.

When the band formed, there really was no intention that “it be anything other than a hobby,” said Tommy. It was a part-time endeavor, such that Jim was able to continue to play with a local bluegrass group, the New Deal String Band. After about six months, the trio decided that they had enough interesting material to do a record, and they got Al McCanless, who knew most of the material, to help out on the album. The Ramblers started working on the record in the spring of 1973. By the time the recording was finished, Mike Craver had joined the band, and he played on one cut.

Mike, 35, was born in Lexington, North Carolina. He took piano lessons as a child and through his high school years. In college, Mike played in a rock and roll band. He became interested in old-time music and started playing it following his graduation from college. Mike has written a number of songs for the Ramblers and some for a solo act that he does in Chapel Hill occasionally. Two of the solo numbers appeared on the band’s album Hard Times (Flying Fish 246). The act itself is “nightclubby,” covering some jazz and some songs from the Golden Age of American popular music.

The Ramblers toured for a month in the summer of 1974, but the members continued to hold day jobs. Mike was a clerical worker in an office, and Jim catalogued books in the public library. Late in 1974, the band became involved in a local musical production about the life of Jesse James. The show, Diamond Studs, went to New York and played Off-Broadway. The Ramblers had acting parts in the show and provided the music. They stuck with the show in New York for the first several months in 1975. “That allowed us to give up our day jobs, have a fairly decent income and focus on trying to find work for the band,” Tommy said,” so that when we left Diamond Studs in August of ’75, we went immediately on our first tour, and we’ve been full-time exclusively since.”

During the Ramblers’ run in Diamond Studs, they began to use Jack Herrick on bass, and early in 1976, they asked him to join the band. Jack, 35, was originally from Teaneck, New Jersey, near New York City. He learned the trumpet from his father, who played. Through high school, Jack played march music and concert band material. In college at the University of North Carolina, he became interested in New Orleans jazz and played in a Dixieland band. Then he switched over to jug bands, including Beebo Buncum’s Jug Jumpers. Following college, Jack moved out west and played some electric guitar and electric bass with country-western groups. His first experience with old-time music was when he played with the Ramblers in Diamond Studs after he returned to the New York area.

Fiddler Clay Buckner, 30,

was born in Cocoa Beach, Florida and grew up in Burlington, North  Carolina.

He played conga drums, harmonica and some mandolin with a band called Fried

Chicken and Watermelon in the Boone, N.C. area. One of the other

band members was T. Michael Coleman, who now plays bass with Doc and Merle

Watson. Clay started learning fiddle around the time that band broke

up. He learned bluegrass fiddle and then got introduced to old-time

music. While still in the Boone area, he met some of the folks who

are now the Cork Lickers, and Clay actually was in that old-time band when

it started.

Carolina.

He played conga drums, harmonica and some mandolin with a band called Fried

Chicken and Watermelon in the Boone, N.C. area. One of the other

band members was T. Michael Coleman, who now plays bass with Doc and Merle

Watson. Clay started learning fiddle around the time that band broke

up. He learned bluegrass fiddle and then got introduced to old-time

music. While still in the Boone area, he met some of the folks who

are now the Cork Lickers, and Clay actually was in that old-time band when

it started.

Over the years, Clay held a lot of different jobs, and one was teaching music. He learned some fiddle technique and began listening to swing and jazz, as well as developing an interest in Irish music. Since Jack enjoyed playing Irish music on the pennywhistle and mandolin, traditional Irish sounds continue to be a part of the Ramblers’ act. One reason Clay particularly likes Irish music “is because you can play a nice long medley of tunes that go through a lot of different keys, whereas you are a little more restricted playing American old-time music if you’re playing with a banjo.”

The Red Clay Ramblers have toured the U.S., Canada, Europe and Africa, and Tommy Thompson can see the difference between the state of the old-time music now and in the sixties when he played with Hollow Rock String Band. “There’s all the difference in the world,” he said. “In the middle sixties…we were part of a loosely connected group of maybe a hundred young people around the United States that had a strong interest, a kind of commitment to the kind of music they were playing then. And we felt very precious about it in the sense that we wanted to focus on it, and keep it focused and concentrate on it. We did kind of define it very narrowly because we didn’t want it to be dissipated. We wanted to understand what we were doing. We wanted to go deep, not spread out in it. So we had pretty rigid ideas about what was legitimate and what wasn’t.

“We wanted to make the heart of our learning process...learning directly from other individual people, as much as possible learning from traditional players rather than from records. We wanted to send our roots into the tradition in as much the traditional way as possible and to keep it that way and to be real careful about what we added to our repertoire and how we did it.” These principles existed, but were unspoken, according to Tommy. “There was a real bond of trying to hang on to and breathe new life into something that seemed very precious, and that brought new life for us, too. It was extremely exciting.

“Now that’s an everyday thing. There’s no longer the need for us or them or anybody else to feel so precious about it, because it’s alive, it’s sprawling, it’s everywhere. It’s been transplanted from the soil in which it was about to die to new soil where it grows and thrives. So, I don’t need to worry about it anymore, so to speak. We can just do whatever the hell we want. A lot of people will think, well, we’re selling out because we’re not playing like we did” in the sixties, “but I know better than that. I know that I’m not selling out a damn thing.”

The Ramblers have been involved in six or seven theater productions over the years, and now Tommy has a real interest in writing for the theater. He spent about three years working with Bland Simpson, one of the authors of Diamond Studs, on an adaptation of Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi. The show was presented in Chapel Hill in the fall of 1982, and the Ramblers provided the music.

At this point, Tommy hopes that the band can make its albums into coherent statements. “What I feel the Ramblers are aiming at” in terms of recording, he said, “Is to take all those threads of all those kinds of music we play and not lose any of them, and yet put out an album that seems like it’s all one kind of music, and that’s Red Clay Ramblers’ music.”

Old-time music, like bluegrass,

draws on the Scottish-Irish and British heritage of the American settlers.

Fiddlers and banjoists played tunes for dances and sang the old ballads.

When old-time bands were recorded in the twenties and thirties, there was

documentation of their response to the world around them. The players

incorporated material from Tin Pan Alley, ragtime and swing. When

the old-time music revival occurred in the sixties and seventies, many

of the bands romanticized the old-timers and attempted to imitate them

as faithfully as possible. The Red Clay Ramblers immersed themselves

in the old-time tradition, but they have gone a step further, to what may

be called the consummatory stage of the music. They have transcended

mere imitation, and while using the vocabulary and carrying the spirit

of old-time music, they have begun to build something new, a music which

is contemporary and responds to their world.

| Back |

![]()