Beating the bluegrass formula

The Red Clay Ramblers make a run at the charts

by John Justice [~1978]

I can just about pinpoint when I started

to get interested in bluegrass,” says Jim Watson. “It was about 1963

and the folk boom was on. I was in prep school in Massachusetts--Mount

Hermon in Northfield. I’d heard a smattering of country music before

on TV, watching it on Saturday afternoons, Porter Wagoner. Then I

heard this song on the radio. It was a record called ‘Aunt Dinah’s

Quilting Party’ by the Country Gentlemen on radio station WBZ in Boston.”

Then, says Watson ’70, “I started learning to back up a friend who played banjo or guitar. We began going to fiddler’s conventions. No, I never went to Union Grove. I was in school in Massachusetts and I couldn’t very well fly down to North Carolina. But we began seeing other good bluegrass musicians and old-time musicians. I didn’t know anything about old-timey music. I didn’t know anything about bluegrass music either.”

In the 15 years since “Aunt Dinah’s Quilting Party” caught his ear and his fancy, bluegrass has taken Watson and the Red Clay Ramblers, the Chapel Hill-based group in which he sings and plays mandolin and guitar, from North Carolina to Winnipeg to Broadway to Brittany.

The quiet but solid success of the Ramblers’ recent album “Merchants Lunch”--good reviews and a respectable 5,000 copies sold to distributors the first year--gives promise that Watson and the Ramblers may well become the nation’s best-known bluegrass band. To put it more accurately, it may become the only bluegrass band to win a national name.

Until now, bluegrass has remained a regional music--the high lonesome wailing of fiddle and mandolin and guitar skimming over and among the hill country of the southern Appalachia, the cradle of bluegrass. But, says Watson, the Ramblers are among a number of groups (he mentions J.D. Crow and the New South and the New Grass Revival as others) trying to break free of the limitations of bluegrass, a musical form as stylized as haiku, and “put their own stamp on the material.”

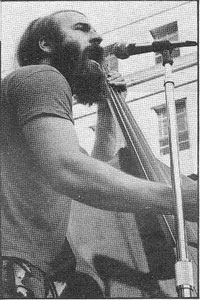

On the sunny side of 30 and on the verge of leaving for a European tour, Watson is an unlikely looking avatar of old-time music. Seated in a Chapel Hill beer joint, his brown hair falling in thick swathes around his bulky shoulders, the amateur weight lifter’s first-glance appearance would seem to place him snugly in the bohemian-beatnik-hippie continuum rather than in the role of performer of a music which is essentially conservative in its origins, content, and form.

When he and the Ramblers appeared at the Chelsea Theater in New York City in 1974 (in a musical called “Diamond Studs,” a loose retelling of the Jesse James story), even as seasoned an observer as New York Times critic Clive Barnes had trouble getting a handle on the group. “Clive Barnes thought we were a cult, like Jacques Brel,” says Watson. “But Barnes wrote the best review of the show, so far as understanding it and liking it.”

South-North cultural encounters were often funny, Watson remembers. “Every night after the play, we’d make a beeline for the bar and we’d beat the audience because all we had to do was lay down an instrument and run. We were in there one night talking to each other and to the bartenders, drinking our beer, or whatever, and somebody heard us and said,” ‘They really DO talk that way.’”

“Studs” was enough of a feather in the professional caps of Watson and the Ramblers that it hastened their decision to go full-time with their music, to forgo day-time jobs and perform their brand of bluegrass with additional instruments (piano, bass, trumpets) and more original material, most of it written by banjoist Tommy Thompson.

But the Broadway experience wasn’t exactly an epiphany for Watson, who says, “Sure, it was exciting at first. Big stars came to see us in the audience. Alec Guiness came backstage and shook hands with everyone in the cast. Leonard Bernstein came, Walter Cronkite.”

The Red Clay Ramblers used the Broadway exposure as a springboard to longer and more far-flung concert tours (appearing everywhere from Staten Island to London to Winnipeg to Williamston, N.C.) Watson says Broadway helped them “get jobs we wouldn’t have got, but didn’t bring fame or fortune.” He now lives in a trailer in Chapel Hill--a trailer with an answering service--and busies himself, between engagements and recording sessions, with practicing on the mandolin and a couple of guitars bought with recent income, working out at a local health club and playing Frisbee at a fairly serious level.

The problem with bluegrass--and thus the problem for the Red Clay Ramblers, Watson, Tommy Thompson, Mike Craver, Bill Hicks, and Jack Herrick--is that you can be the best, most talented bluegrass band in America and nobody knows who you are.

“We’re sort of realistic about the potential audience for bluegrass,” says Watson. “Bluegrass has sort of a relentless beat. Its form and repertoire are so limited that you could take some singers--a lead, tenor, baritone--and the instruments--banjo, bass, guitar, mandolin--and in an hour, they could get together a decent show.”

Watson does see possibilities for the Ramblers in diversification of their sound and material, combining bluegrass with what he calls old-timey music and the inevitably modern sensibilities of the Ramblers. “Old-timey music had an incredible variety of sounds, regional sounds, the North Georgia sound. There was Gid Tanner and the Skilletlickers, a PREE-mier band,” he says. The old-style music, he says, was varied enough that you can find Louis Armstrong playing on at least one record of Jimmy Rodgers, a white deep-country blues singer who recorded during the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Watson is fond of many old groups--the Carter Family, Charley Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers, and others known only to aficionados of old-timey music. “The problem is to transcend the formula,” he says. “I think we’ll do well; we’ll probably continue to be in demand on the level we’re at now at least. Partly because we’re diverse. I mean, some people may not like the old-timey stuff but may like Herrick’s trumpet or the singing so they’ll be willing lend us an ear.”

After playing the Chapel Hill area in 1969

with Tommy Thompson, up from a teaching job, Watson played guitar in 1972

with the New Deal String Band, and then became a member of the Red Clay

Ramblers. The rest is history--the small-scale history of a musician

and a group doing well enough that the great dream of a breakthrough seems

possible--a history whose ending remains to be seen.

| Souvenirs |

![]()